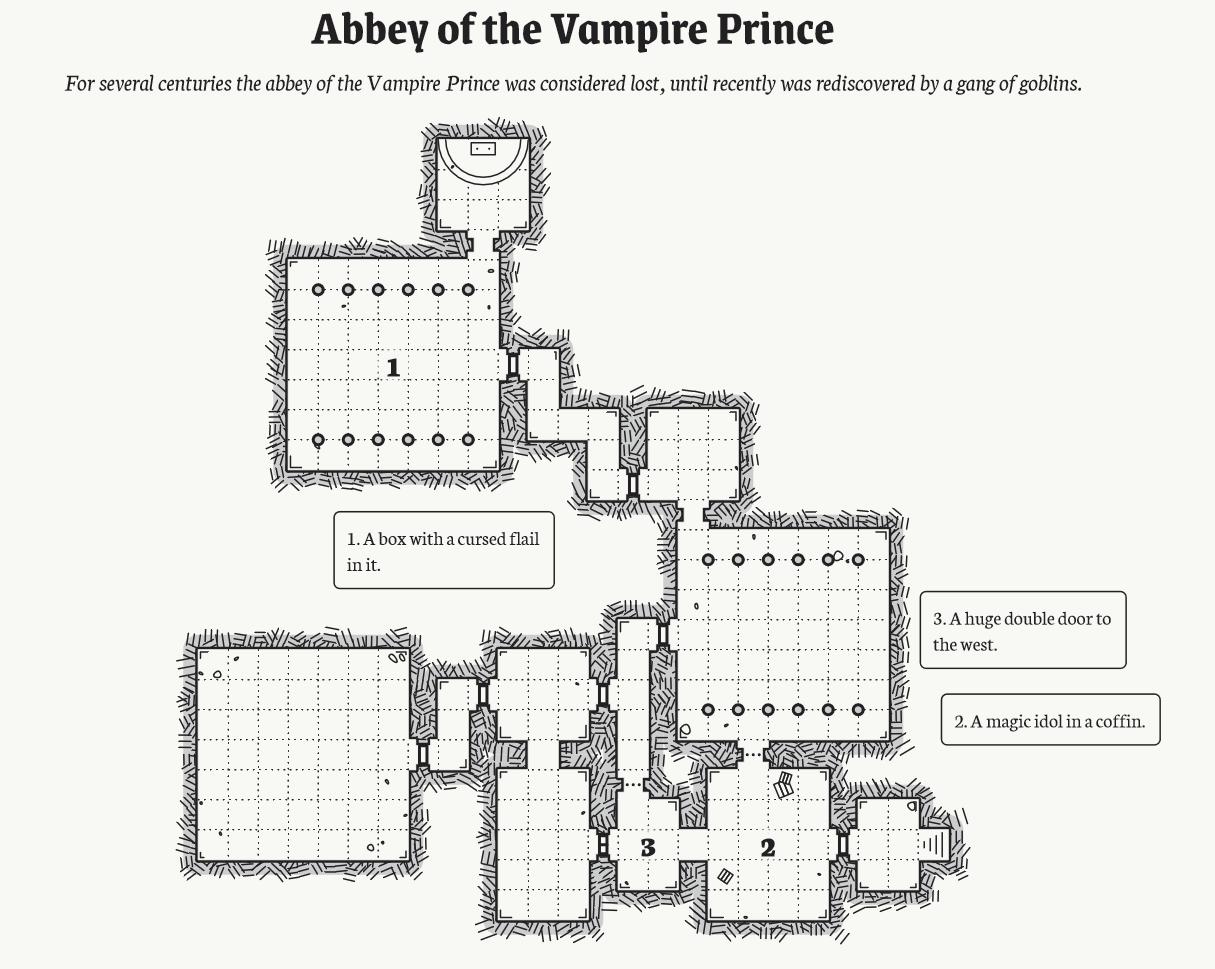

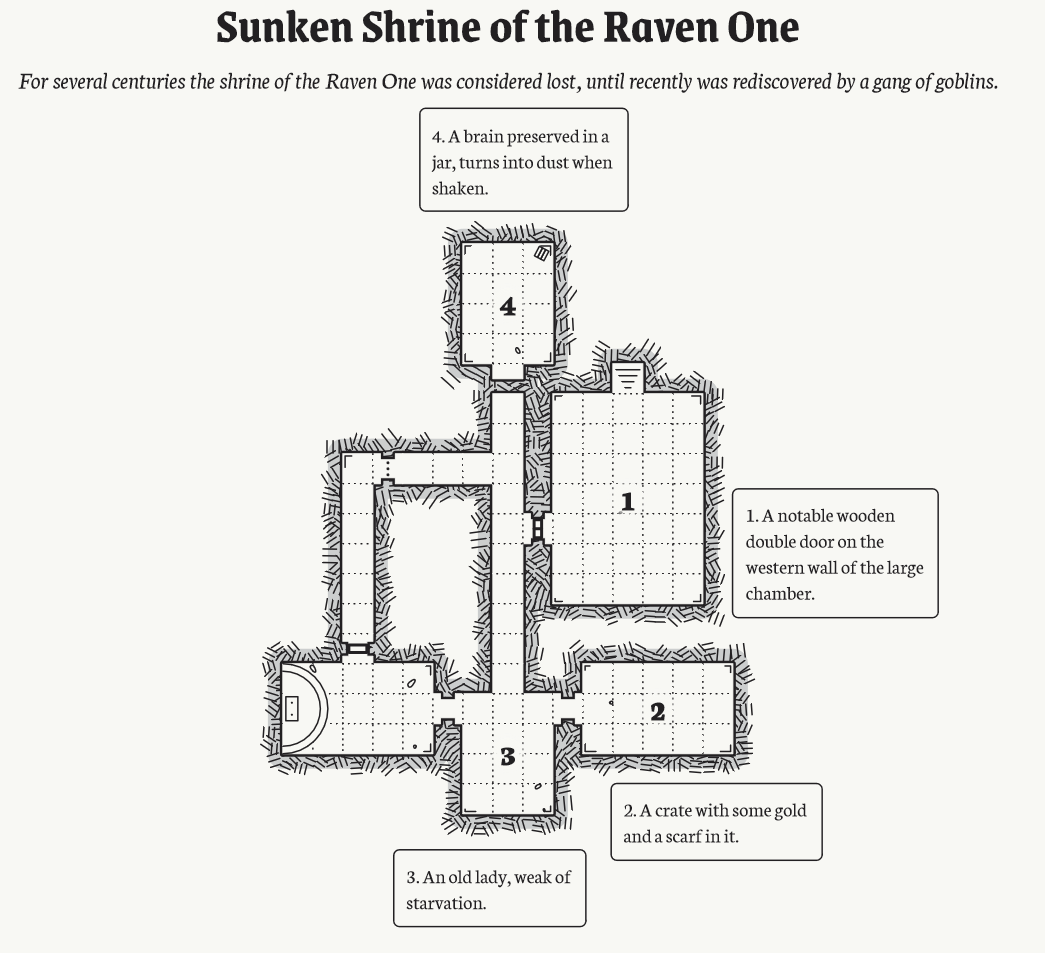

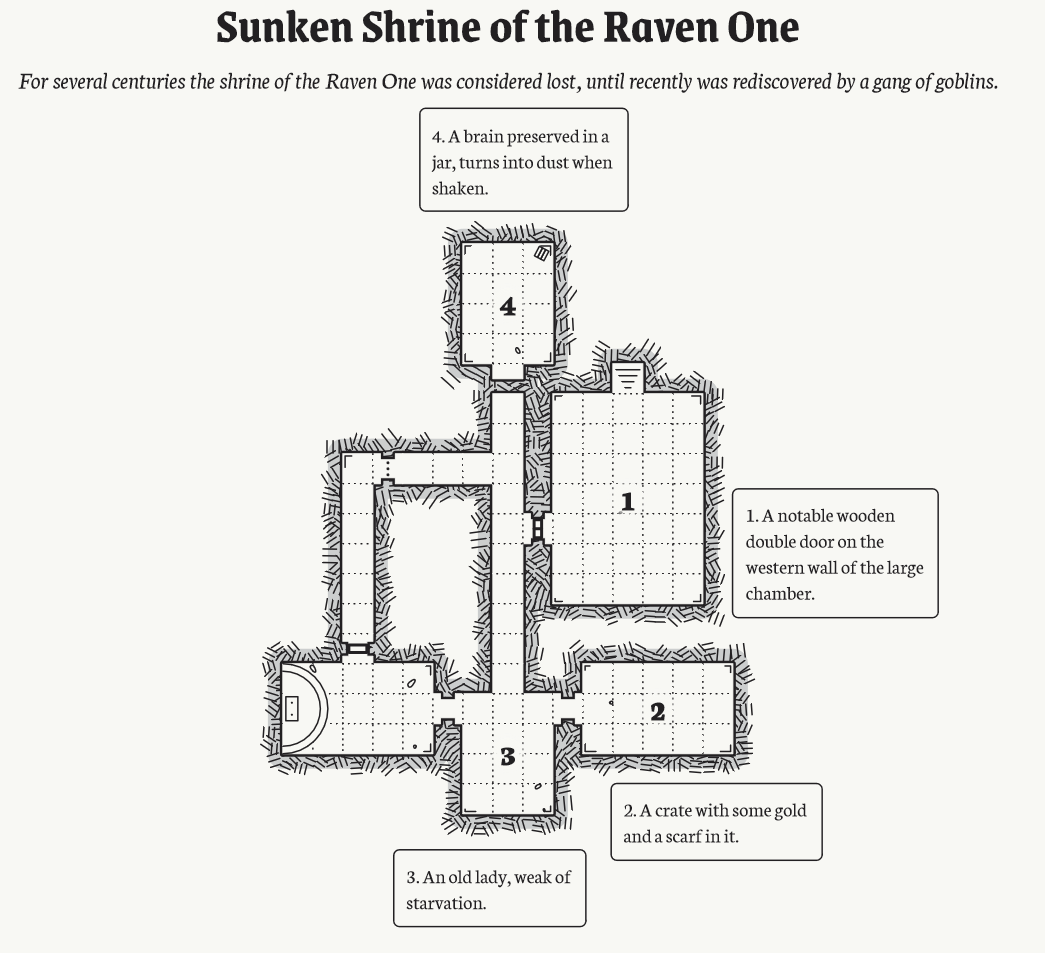

One Page Dungeon generator

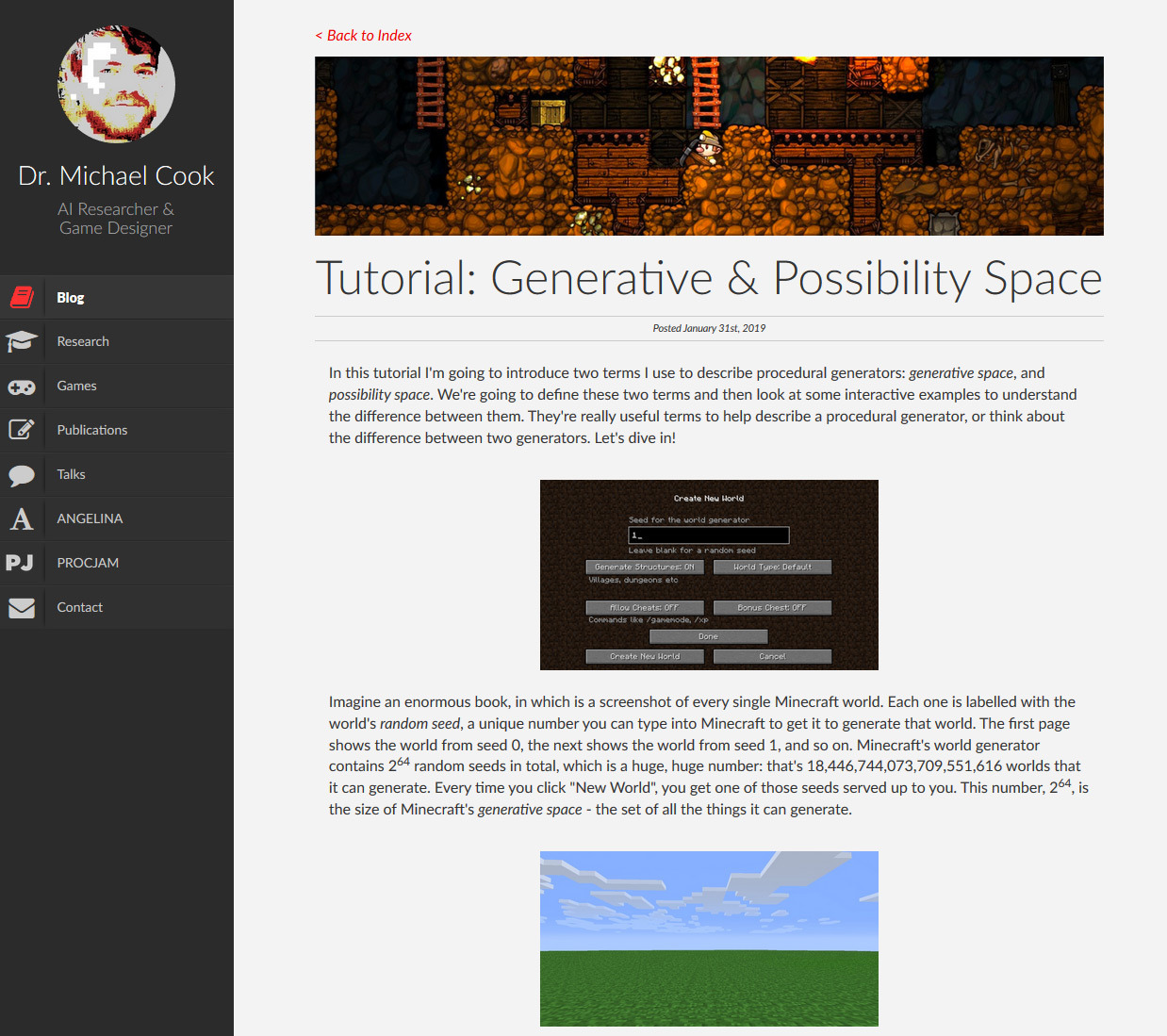

This one-page dungeon generator by

Oleg Dolya

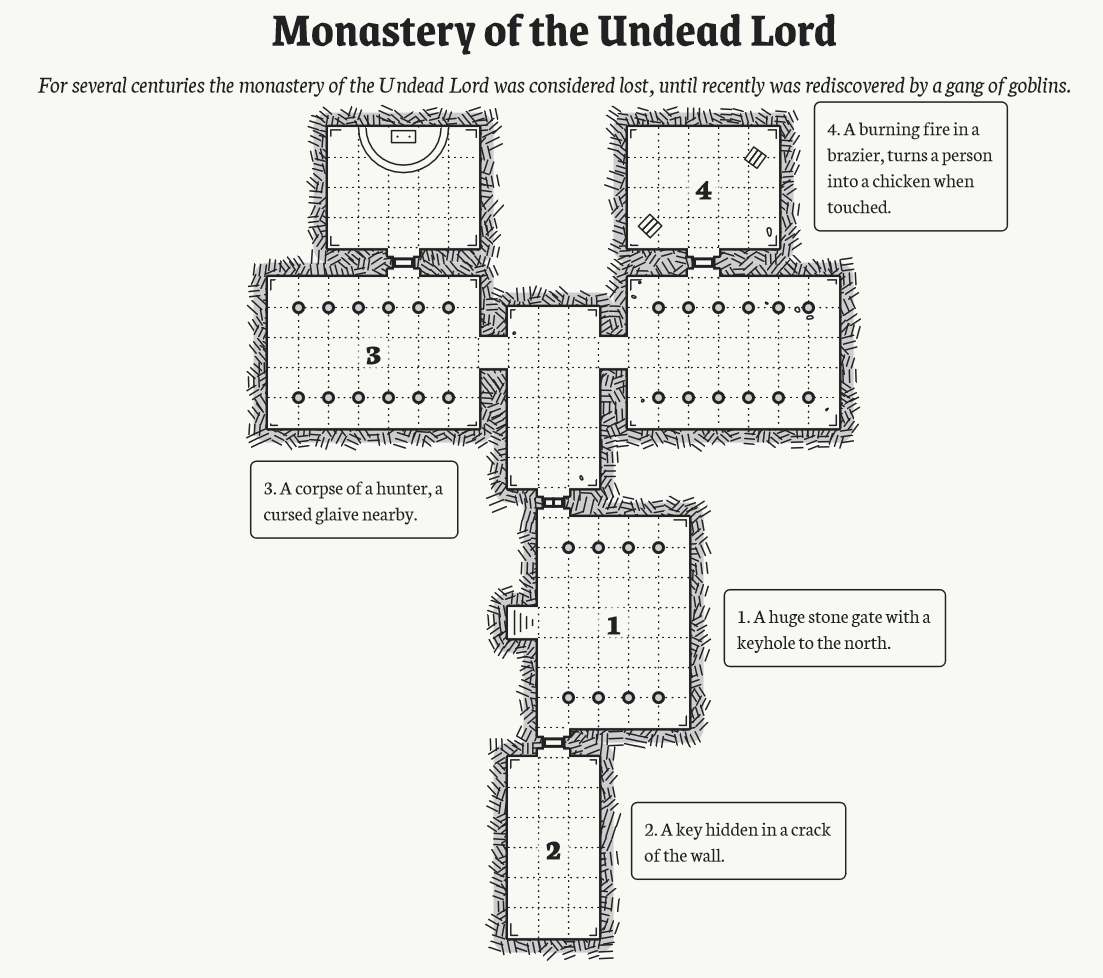

(also known for the Medieval Fantasy City Generator) goes beyond the basic throw-rooms-together dungeon generator to have a focus on content. It includes descriptions and room prompts, often with implied connections between keys and locked doors.

There’s a number of ways to add more structure to content like this, including cyclic dungeon generation, but one of my favorites is a little similar to what appears to be going on here with the keys.

Without looking at the source code, the design pattern behind the keys appears to be: 1. have a locked door 2. place a key in a room that can be reached without crossing that locked door. Pretty simple, but creates interesting structures for the players to discover. This can be elaborated to include a chain of things that the player can encounter and piece together the entire story.

One place I’ve seen this used to great effect is Emily Short’s Annals of the Parrigues, with some of the footnotes: a series of footnotes is written in a way that describes an arc, and then the generator is allowed to include the next element from the arc when it feels like it.

If you wanted to make a dungeon generator like this, you could add pairs or triplets of elements to include. A simple one might be a monster, its lair, and it’s most recent victim. Because you are hand-writing these element groups, you can make sure there’s an implied story or relationship. If you’ve got enough of these, mixed in with the rest of the content, they will still feel interesting even if the player sees them a few times.

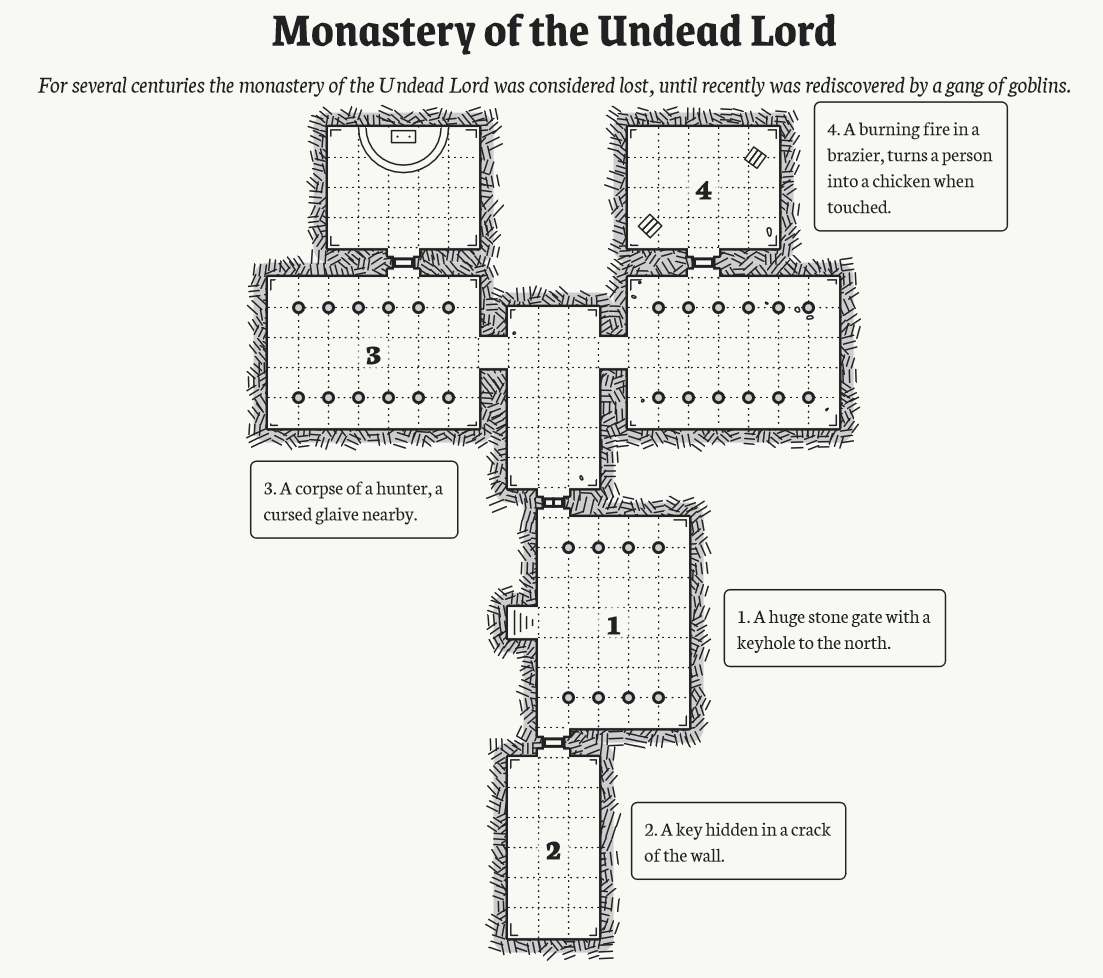

Another related form of content to include is a recurring motif. Right now the One Page Dungeon generator creates a lot of dying elves in corners and similar things, which a skilled Dungeon Master could spin into a story. But promoting too much mushroomy content can feel like the generator is making a mistake. Pushing the uniqueness of the elements makes it look deliberate.

One thing that King of Dragon Pass (and Six Ages) has taught me is to not be afraid of being specific! Finding the coral-encrusted Mirror of the Dark Wizard Archronalax and the coral-encrusted throne of

the Dark Wizard Archronalax

will make the players start to wonder where the coral-encrusted magic wand of

the Dark Wizard Archronalax

is. Having some hyper-specific elements that are spread out across many generated maps gives the generator character.

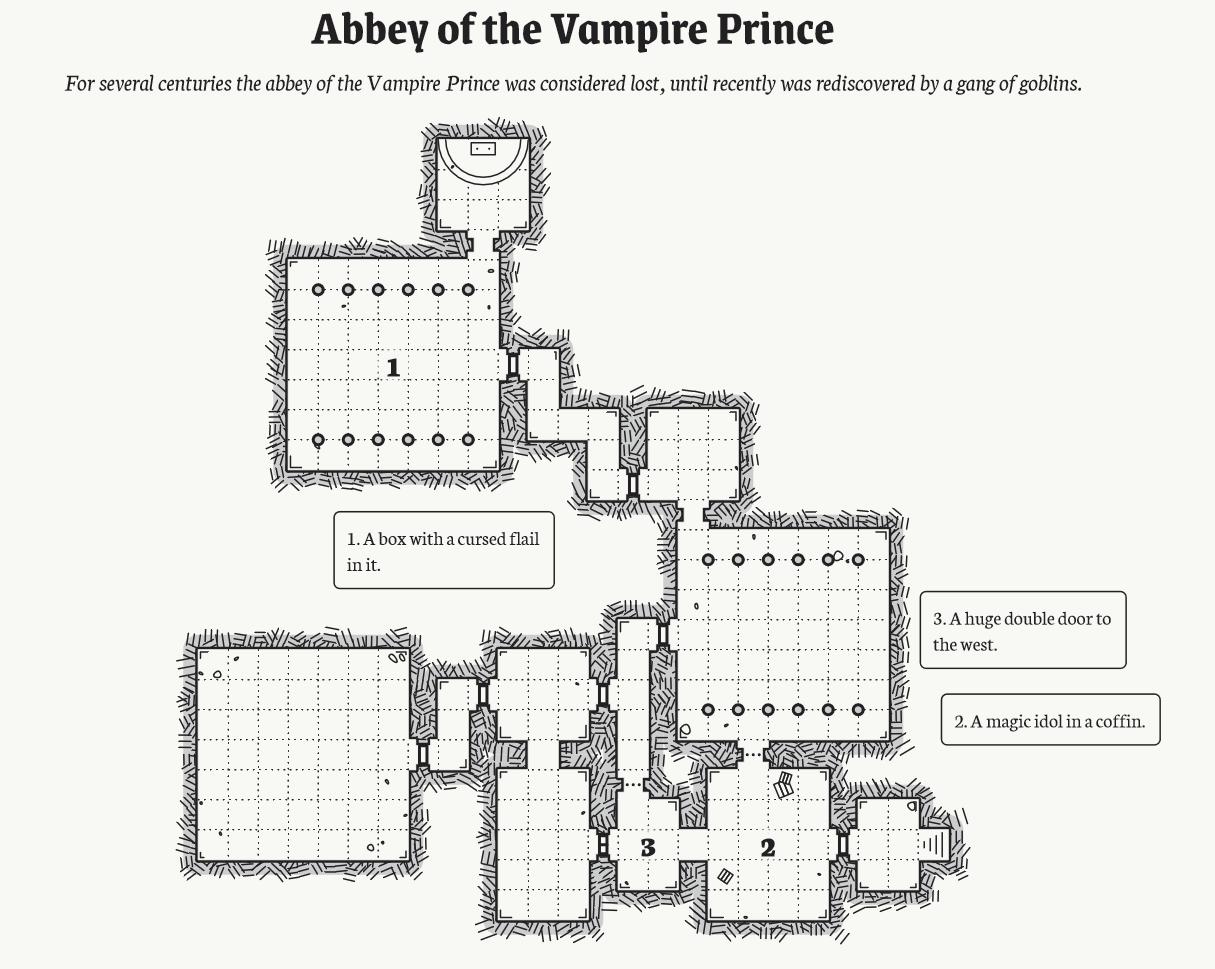

Think in terms of motifs, of aesthetic signals that can tie different parts of the generated level together, of ways to create emergent resonances between independently generated elements. Which brings me to my last point for now: the simplest way to have elements in your generator work with each other is to write them with a lot of suggestion and storyful-ness. One Page Dungeon is pretty good at this already: A reinforced coffin containing a blood-spattered spear and a cursed hammer? There’s clearly a story behind that!

While there are many existing dungeon generators, there’s plenty of room for new generators that have their own character and ways of telling stories.

There’s lots of space for more dungeon generators to explore!

https://watabou.itch.io/one-page-dungeon