Dwarf Fortress

When we’re talking about procedural generation, Dwarf Fortress is the skeleton zombie elephant in the room. There’s a nearly infinite number of procedural generation topics to discuss when it comes to Dwarf Fortress, so it’s hard to know where to start.

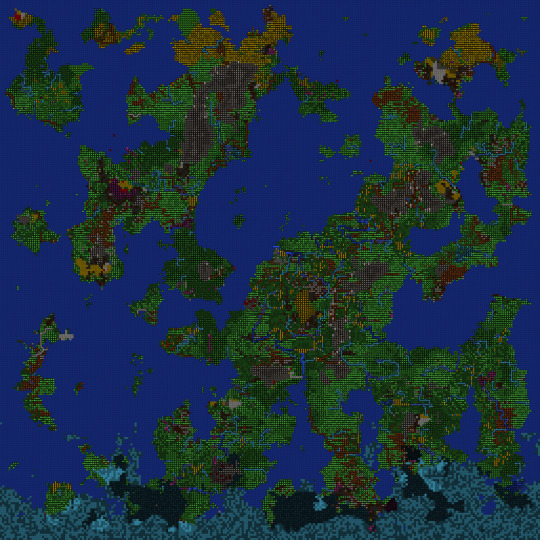

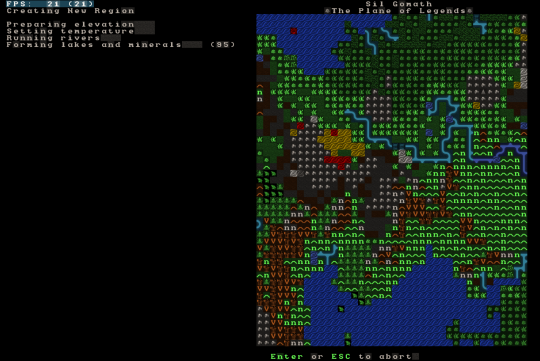

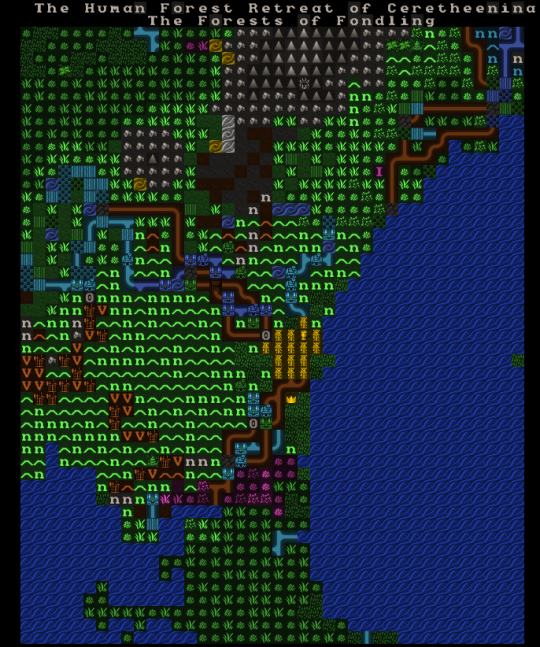

So let’s start where the game does: with the creation of a world.

The map generation part is fairly straightforward, though it models details like climate, vegetation, savagery, good, and evil. It goes through a set of phases, placing elevation, temperature, rivers, and so on. Each phase may be rejected if it fails to meet the minimum playable criteria.

It then simulates centuries of history to create an elaborate backstory for every place and culture you’ll encounter in the game.

This is a textbook demonstration of the degree of overkill Dwarf Fortress brings to everything. Most of the details here have little effect on a playable fortress.

But the historical events are recorded as legends, which can show up in your dwarves’ artwork. And you can visit many of the historical sites in Adventure Mode, and even encounter some of the long-lived creatures that inhabit the generated world.

That attention to detail is the basic theme of Dwarf Fortress. That’s why it has legions of dedicated fans who overcame its inaccessible interface to mine out the gems hidden within.

You don’t have to go to Dwarf Fortress’s lengths to see the benefits of a generated history, though. Usually, when people talk about the history generation, they focus on the emergent complexity it creates: an elf raised by dwarves who rises to rule their kingdom and slay a megabeast, a poet invents a new kind of poetry and teaches it to her students, who use to to write epics about the elf king of the dwarves and so on.

But creating a history for these worlds and remembering it has another consequence, one that doesn’t require quite so much emergent complexity. One thing that gives objects in the real world meaning is precisely that they do have a history. Even the most mass-produced object has a kind of metaphysical metadata that digital instances of a 3D model lack.

By manufacturing a history for these procedurally generated objects, we can give them a little bit of this complexity. Linking the different people, places, and things in the world helps escape the trap of many systemically identical cookie-cutter results, one of the traditional weak points of procedural generation.